Foul Trade Read online

Page 2

‘It costs money and his parents don’t have any.’

‘I haven’t got any parents but I’m still clean.’

This was familiar - but dangerous - territory which Alice trod whenever she felt she was being unjustly criticised. May could feel the melancholy of the day returning. She patted Alice’s hand.

‘So, what’s this about elephants?’

‘There’s a show opening at the Hippodrome that’s got them in. Stin... Sid knew all about it. His dad works in the printers where they do the posters and the man who books the acts let it slip. He told him not to tell anyone but that’s just a trick because advance publicity is worth at least a hundred tickets.’

May was impressed at how quickly Alice had picked up an appreciation of the theatre business. They had been back under the same roof for nearly two years but she was still discovering new depths to her sister. They had arrived at Chrisp Street. The market took up the entire length, the canvas tilts of the closely packed stalls jutting out to all-but cover the roadway. It was at its most crowded in the evenings - at pub-throwing-out time you were as likely to get your thoughts jostled from your head as drop a penny without the space to bend down to pick it up. May enjoyed Chrisp Street best when it was up to the full-scale riot proportions of a Saturday night. The shriek and babble of languages fresh off the ships; the joy of the conquest as she snatched exactly what she’d been looking for from under the hand of a less determined bargain-hunter; elbows in ribs, crushed toes, and sometimes a glancing blow to the side of the head; the welcome respite of a plate of whelks and a cup of tea at the stall on the corner of Carmen Street before doubling back and doing it all again on the other side. But even a Tuesday late afternoon was never dull.

As usual, the first hawker they came to was a man selling pots, pans, and white china. He rattled a wooden spoon in a zinc bowl in a half-hearted effort to attract her attention but both of them knew it was merely a rehearsal and he expected nothing to come of it. But May did stop at the fruit stall spanning the frontage of the chemist shop and bought some oranges, refusing to let the stallholder select them in case he sneaked some rotten ones into her bag. Alice was skittish beside her. The girl had so much energy it made May tired to watch so she switched her attention to wondering if she should splash out on some brazil nuts. The smell of vanilla toffee was making her mouth water. She paid for her purchases and drifted on.

They were at the eel stall now and May had to stop. Not only to rest her feet. The tanks of writhing fish had always held a grisly fascination. The stallholder pulled one out by hooking his fingers under the gills.

‘Get in ’ere closer, mother, I’ve got a right tight grip-’

The woman next to May shuddered but stepped forward.

‘-or so my old lady says. And if he does slither out it’ll be no more worse than that trouser-snake I reckon you know how to ’andle.’

Like a veteran of the boards he waited for his audience’s laughter to reach its peak and then lifted his cleaver to shoulder height - twitching his wrist a little so the metal glinted - and brought it down at the same time as releasing the eel. Whack. The blade severed the head, the wriggling body sliding in its slime off the marble slab and into a pail. The fishmonger had never missed in all the years May had been watching, and neither had any corpse.

Alice was no longer by her side. May looked around for her but could only see middle-aged and elderly women clutching shopping bags. She walked on to where the haberdashery stalls were sandwiched between a collection of thrown-together furniture, looking for all the world as if the bailiffs had just completed an eviction and dumped it there. She was fingering a bolt of cotton printed with tiny sprigs of flowers when her sister finally joined her.

‘You reckoning on wearing an apron?’

‘I thought it’d make a charming dress.’

‘What? And have everyone in the theatre wet themselves laughing?’

‘You used to like patterns like this.’

Alice rolled her eyes. ‘When I was a kid.’ She reached across and unfurled a garish concoction of yellow and black. ‘How about this?’

‘It’s silk. You know I can’t afford that. And besides, why would you want to go around looking as if you’re covered in squashed wasps?’

‘Reckon I’d rather do that than have people think I work in an undertaker’s.’

May found herself pulling the edges of her coat closed to hide the offending white blouse and charcoal skirt. Alice was going through a phase of thoughtlessly sharpening her tongue, turning everything - even what was supposed to be a treat - into a skirmish. But May was tired and really couldn’t be bothered to fight.

‘This one then?’ Bright red poppies on a buttermilk background. Surely Alice couldn’t be afraid of blending into the background sheathed in that?

Alice shrugged. That was as much approval for her choice as May was going to get. She attracted the stallholder’s attention and ordered three yards.

‘Is it all right if I go to Elaine’s now? I mean, you don’t need me for anything else do you? Her ma’ll give me supper.’

‘Go on, then. But don’t be in late. Remember you’ll be working the evening shows for the rest of the week.’

Alice gave her such a don’t fuss look that May cuffed her lightly on the shoulder before elbowing her way into the gaggle of women surrounding the tripe dresser.

***

‘You should’ve heard him. Making out like I ought to be grateful that he would even consider a shiddach with a cripple.’

Sally’s shears slid through the material without a stutter. May’s closest friend, she was a thirty-year-old dressmaker who lived and worked above her father’s tailor shop. She had a mass of blue-black wiry hair, brown eyes, and downy olive skin. Born with one leg shorter than the other and a spine that resembled a drooping flower stem, she was destined to be forever making pretty clothes to drape figures more perfect than her own. But pity was the last thing May ever felt in Sal’s company; they shared too much for her ever to allow herself to do that.

‘You want another cuppa? Help yourself.’

May did so. Sally drank her tea the Russian way, black with a slice of lemon. It had all the restorative qualities of a magic potion.

‘You could make a good match if you stretched to the effort. All those professionals you see in court, one of them will make an offer if you’d agree to meet them at least halfway in the game. With time, even a bear can learn how to dance.’

May picked up a spoon. She clattered it against the china as she stirred. ‘I’m perfectly happy as I am thanks. You know you asked me if I could do something about that chair of your grandmother’s, I saw a broken one in the market and it’d be easy to swap the legs over; I’ve got all of my brother’s tools in a box under the stairs.’

May caught Sally looking at her from under her frizzy fringe as she hobbled to the end of the worktable.

‘It’s not good to be alone, even in Paradise.’

‘Just as well I’ve got Alice then.’

‘What makes you think she’ll be staying around here for any longer than she has to? Got grand notions of herself, that one, and any day now we’ll all be coated in the dust she kicks off her heels.’

‘Not if I have my way she won’t. I’m biding my time until the novelty of being surrounded by stardust wears off then I’m going to persuade her to take an office job with normal hours and go to night school. She needs some professional qualifications if she’s ever going to get anywhere in this world. Everything else is too stacked against the working classes for the likes of us to break out of the patterns of poverty.’

As May said it she could see her father thumping his fist on the kitchen table. He’d been a staunch Communist but she hadn’t realised how much some of his views had become her own until this moment. But she didn’t want to thin

k about him.

‘What do you want for all your efforts, thanks? She’s just seventeen. At that age we all think our elders and betters know nothing. It takes time for us to realise that the tapping on the door is not a call to arms, but wisdom. And it’s unfair of you to expect Alice to be any different. You want a life that is yours to control? Then do as I suggested and get a husband. And don’t even bother to tell me you are still mourning over that Henry Farlow because I won’t believe you. I happen to know that you weren’t really in love with him.’

‘We were extremely fond of each other. From what I’ve seen of many marriages around here, that’s more than most can say. And it would have worked; we were suited.’

‘Cloth can be cut one way or the other and made to fit. If you persist in refusing to even take the measure of a man, then the few still around will be snapped up and you’ll only have a lonely old age to keep you company.’

‘There’s never any guarantee against that; three-quarters of the women down my street expected to have their husbands by their sides forever before the Great War came.’

‘That’s as may be but you could at least not throw the bolt across the door yourself. Stop treating every man like a brother. Also try acting a little helpless once in a while. With such big sea-blue eyes and thick dark hair for which a wigmaker would gladly pawn his grandchildren, you should have no trouble having the luxury of picking. And that would be true even if you weren’t blessed with a figure most of my clients would have to starve themselves to get. Just because you have a man’s job doesn’t mean you have to hide your feminine charms; it’s only throwing it back in God’s face to be so wasteful. Not to say rubbing it under the nose of the likes of me.’ Sally wasn’t smiling.

May refused to let the airing of her faults prick her. Sally meant well, she just had a very different view of life. One based on marriage and babies as being the most natural and noble state for women. It pained May to realise how keenly her friend must feel it was something she would never attain.

Sally had resumed her cutting. ‘You could do worse than taking a tip or two from Alice; she knows already how to use what God saw fit to give her.’

‘Why do you think I worry about her so much? She thinks she’s a woman but in reality she’s little more than a child.’

‘That has nothing to do with her age. She’ll be just the same when she’s thirty. Your sister is a flirt who knows the precise extent of her power and how to use it to be granted anything she wants. The sooner you realise that, the easier a time you’ll have of it. Stop trying to change her nature and wise up to her instead; if she’s bucking against the reins now, she’ll be off looking for soft hay to roll in before long. You mark my words.’

May had to stop from asking Sally what she knew about it - with five brothers it was probably a damn sight more than her.

‘I happen to think she’ll come good. All she needs is a bit of sense drummed into her and a little steering in the right direction. Like getting this dream of hers about being an actress out of her head. Seems it’s what she’s... wanted for ever and ever... which is strange as she’d never so much as mentioned it before she’d started at the theatre.’

Sally interrupted her cutting with a sort of hiccup of the shears on the table.

‘Why would she choose you to share the secrets of her heart? She is not the uncomplicated girl who waved you off when you boarded the ship to France, and you are not the same sister who came back. Life and circumstances have changed you both. Get to know the person she is now before she surprises you with something that will cause you both more pain than choosing a profession you think not good enough for her.’

That hadn’t had the lightness of loving mockery. May took a sip of tea to stop from leaping to her own defence.

‘It’ll be altogether too rackety a life.’

‘And you and I know each day where the next month’s rent’s going to come from? My aunt played the Yiddish Theatre in Commercial Road for years and she always had food in her mouth and a bed to fall into at night. Even managed to bring up four children who no one could say were any more wanting than the others in the street, despite uncle never lifting a finger over the shock of having to leave the shtetl.’

Sally was trying to turn it into one of her jokes about the hopelessness of all Jewish men but May couldn’t raise a smile. She knew Alice would be more susceptible than most to the temptations the theatre world had to offer. After a life touched by so much grief - eighteen of her schoolmates killed in a Zeppelin raid; losing her mother to influenza; her brother now no more than a name on the Roll of Honour; and finally... finally... having a suicide for a father - what young girl wouldn’t be spurred on to taste every experience on offer out of fear her time on this earth could be cut short at any moment?

No, for as long as they were living under the same roof May was going to make sure her sister set her feet on the right path. And, one day, Alice might even thank her for it.

Chapter Three

The stage door was tucked down at the end of the passage, a boxed light announcing the recess in the soot-etched wall. It was no different from all the others she’d arrived at - a little shabbier, perhaps; certainly the management hadn’t bothered with a lick of paint in some time - but to Vi Tremins, character actress and occasional revue turn, it promised all the excitement of an opening night. The Gaiety Theatre had once numbered amongst the most popular Music Halls in the East End and still played twice daily with an enviable reputation in the business for being packed out on Friday and Saturday nights. Only, on this occasion, it wasn’t the prospect of playing to a full house that was making her chest flutter.

Once over the threshold the familiar smells of rabbit-skin size, stale sweat, and insufficiently-dried canvas filled her nostrils. Vi took a moment to savour the sense of coming home. The small space was almost fully-occupied by a figure swaddled in outdoor things against the chill damp of the morning fog. As an expert in discerning character even under the heaviest of disguises, Vi glanced at the only flesh on show - a neat pair of ankles - and decided they belonged to a girl who’d not long packed away her ragdolls. The doorman - the usual type with pasty indoor-skin, and a cigarette hanging from the corner of his mouth - was leaning through the window of his cubbyhole, entertaining his visitor with what sounded like one of the backstage stories Vi herself had been weaned on.

‘...so I says to the string of water, I says, you get yourself down there, ghost or not ghost, and you pull that lever when you’re told or it won’t be no ’eadless ’arry you need be affrighted of because ol’ Swinburn’ll ’ave your guts for garters before the tabs come down close of second act.’

The back of the coat shuddered like a sack of kittens poked with a stick. Vi smiled. The poor thing was probably due to clean under the stage or something and now she’d spend her entire time jumping at every strange shape and shadow.

‘What can I be doing for you, love?’

‘I’m Violet Tremins, engaged to get the talent show up and running.’

The girl spun around as if the hem of her coat was on fire. ‘A talent show. Here? Really? Are you all booked up, I mean, are there any spaces on the bill? I can sing... a little.’

Despite a dreadful woollen hat pulled down over her ears and a scarf wrapped over that to obscure her hair, Vi was treated to a glimpse of bright doe eyes, clear skin, and cheekbones that would defy the flattening effect of greasepaint. Even if the girl was no Marie Lloyd she would be pleasing enough to look at and, provided she could hold a tune long enough to get through a verse and two choruses, would probably escape the indignity of having things thrown at her. She was certainly worth the trouble of an audition.

‘Try-outs are Saturday week, immediately following the afternoon performance. Why don’t you come along? But I warn you that if we offer you a slot it’ll be nothing but hard work - the show’s to be at the

end of April and we only have stage time for five rehearsals.’

‘I work here in the box office and can ask the manager to get my shifts so as I can be on stage whenever I get the call. And in the dead times I’ll lend a hand with anything you want doing - you know, putting posters up and stuff.’

Had she ever been so starry-eyed herself? It was rather sweet. ‘Don’t go getting carried away... you’ve got to get through the audition first. And, if you do, even then it will only be a mid-week afternoon performance; the management isn’t going to risk losing a drop in Saturday night takings.’

‘I don’t care, really I don’t... to be in a proper show, in a real theatre... it’s all I’ve ever dreamed about.’

The doorman grunted. ‘Put a sock in it, will yer? All this dog-with-two-tails palaver so early of a morning’s giving me ’eartburn. The guvnor’s already in, love. Take yourself through; you don’t look like you need a map.’

Vi walked up to the swing door which separated the civilians of the street from the theatre professionals. She sensed the girl looking at her enviously; not even front of house employees were allowed through this hallowed entrance. Vi reached into her handbag.

‘Here. A gift. It’s an old tradition for a board-hardened actress to give a newcomer a little something before her first audition. Wear it to bring you luck.’

It was only a half-used tube of lipstick but you’d have thought she’d just handed over the key to His Majesty’s Theatre’s star dressing room. Vi left the girl caressing the case in her gloved fingers as she plunged through into the dimly-lit and dusty world of make-believe.

Chapter Four

May shepherded the three women across the road. The only members of the public she’d called to attend Clarice Gem’s inquest, she’d suggested they wait in the coffee house until the appointed time. She hadn’t wanted Mrs Gem to be in the vestibule and encounter the jury coming back from the mortuary; their faces would’ve made it only too clear that they had just visited her cold and silent daughter.

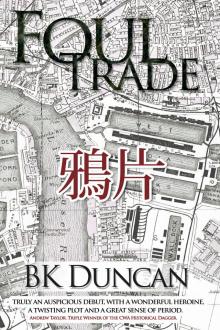

Foul Trade

Foul Trade